|

This exhibition presents portraits, sculptures, drawings, and rare books that illuminate the first 100 years of the Society of Dilettanti.

The society was founded in 1734 in London as a dining club for British gentlemen who had made the Grand Tour, an extended trip to Italy for cultural enrichment. The Dilettanti combined revelry and witty irreverence with serious study of antiquity. They sponsored archaeological expeditions, assembled celebrated antiquities collections, and elevated classical art and architecture as models of refined taste and style.

Read more about the society's history below, or explore highlights of the exhibition in the exhibition slideshow.

|

|

|

|

Bouchier Wray (about 1714–1784), Sixth Baronet, George Knapton, 1744. The Society of Dilettanti, London

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Society of Dilettanti was dedicated to "encouraging, at home, a taste for those objects which had contributed to their entertainment abroad." The group's name introduced the word dilettante (from the Italian dilettare, "to delight") into English and celebrated the interests of the amateur. From informal gatherings in Italy to ceremonial meetings in London, the Dilettanti cultivated a sense of kinship and conviviality. Seria ludo (Serious Matters in a Playful Vein), one of the group's principal toasts, expressed its blend of the learned and the lively.

George Knapton's portraits of various prominent Dilettanti convey the spirit of Seria ludo. Here, in the cabin of a ship under sail, the Dilettante Bouchier Wray ladles punch from a bowl inscribed with a line from the Roman poet Horace: Dulce est desipere in loco ('Tis sweet at the fitting time to cast serious thoughts aside). George Knapton's strong diagonal composition conveys the tilting motion of the ship and Wray's vivacious offer to fill the viewer's cup—appropriate for a society that honored Bacchus, god of wine.

|

|

|

|

|

Temple of Apollo at Didyma (detail) in Antiquities of Ionia, after William Pars, 1821

|

|

|

|

In the mid-1700s, members of the Society of Dilettanti began to sponsor expeditions to the Middle East, Greece, and Turkey, and to publish the results. Their aim was to produce empirical drawings of the most famous, but little understood, monuments of antiquity. Passionate precision was a hallmark of the society's books, which heralded the development of archaeology as a rigorous scholarly discipline.

One of the Dilettanti's most significant books was The Antiquities of Athens Measured and Delineated, published in three volumes between 1762 and 1794. Inspired by its success, the society launched a two-year expedition to Ionia (in present-day Turkey) in 1764. As leader they chose the classical scholar Richard Chandler, accompanied by architect Nicholas Revett and topographical artist William Pars. From their base in Smyrna (present-day Izmir), the three were directed to "procure the exactest plans and measures possible of the buildings." In this plate from their resulting book, Antiquities of Ionia, Revett uses calipers to measure a fallen block between two upright columns.

|

|

|

|

Statuette of Priapus, Roman, A.D. 1–200

|

|

|

The rituals of the Dilettanti intertwined sex and religion. Members created cabinets of erotic curiosities, which displayed what the 18th-century poet Alexander Pope satirically described as "statues, dirty gods, and coins." They collected and interpreted these "dirty gods" as specimens of ancient phallic cults. Excavations at Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae uncovered troves of sexually explicit objects, providing evidence for such cults.

This statuette depicts Priapus, the god of male sexual potency. Priapus was cursed by the goddess Hera with ugly features and an enormous phallus. His protruding genitals provoke laughter, a response that was believed to ward off evil spirits. As the god of fertility and protector of gardens, Priapus is often shown carrying a basket of fruit.

Leading Dilettante Richard Payne Knight wrote a daring treatise on the worship of Priapus, which was published by the society in 1786. It argues that all art is grounded in religion, and all religion in sexuality—or, "the worship of the generative powers." The popular press responded with scathing attacks on antiquities collectors in general and on the Dilettanti in particular.

|

|

|

|

|

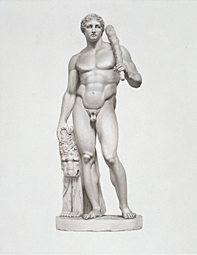

The Lansdowne Herakles, John Samuel Agar, 1799–1807

|

|

|

|

The Society of Dilettanti counted among its members the foremost British connoisseurs of classical art. Connoisseurship pivoted on virtù, a term denoting both fine-art objects and the ability to discern their aesthetic value.

Richard Payne Knight was the embodiment of fashionable taste and the Dilettanti's arbiter of artistic quality. Knight praised the Lansdowne Herakles, which was owned by William Petty, first Marquess of Lansdowne and Britain's prime minister, as "incomparably the finest male figure that has ever come into [England]."

Knight commissioned artist John Samuel Agar to create a series of highly finished drawings of classical statuary in British collections, including this expressive rendering of the Lansdowne Herakles. Agar's illustrations are among the finest ever made of sculpture. They served as the basis for the stipple engravings in Knight's publication Specimens of Antient Sculpture, which rivaled the high standards for precision set by the society's architectural publications. The illustrations pay tribute to the best classical sculptures in England, and to the stature of their Dilettanti owners as tastemakers.

|

|

|

|

The Golden Asses (detail), Thomas Patch, 1761. The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Dilettanti were avid collectors of antiquities, which they acquired during their extensive Mediterranean travels. Thomas Hope, for example, owned some 1,500 Greek vases. Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin, brought to London marble sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens. Controversy over the artistic merits of the Elgin Marbles divided the society, but their acquisition by the British Museum ultimately fulfilled the Dilettanti's core mission—to champion classical antiquity for the improvement of the arts and taste in England.

Many of the works of art collected by the Dilettanti entered American museums when prominent British collections were dispersed. American newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst bought a number of Thomas Hope's vases, for example, later donating them to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. J. Paul Getty acquired the Lansdowne Herakles once owned by William Petty as well as a Mixing Vessel with a Chariot Scene once owned by Hope. Many objects in the J. Paul Getty Museum, in fact, can be traced back to Dilettanti collectors of the 18th and 19th centuries.

In a group caricature from 1761, a detail of which is shown here, artist Thomas Patch presents fanciful versions of the artistic spoils acquired by the Dilettanti, including antiquities, mythological paintings, and chinoiserie. The artist portrays himself astride a gold statue of an ass, an allusion to the satirical poem "L'asino d'oro" by Niccolò Machiavelli. The inscription on the base brands the aristocratic sitters as "asinine" fops.

|

|

|

|

|